Scientists think they just invented “multifunctional polyculture” food farms, but it’s been around forever as “food forests” and “permaculture”

08/24/2017 / By Isabelle Z.

University of Illinois researchers have announced that they have discovered a way to design a landscape that can provide people with a range of nutritious foods while earning a profit. Of course, this “news” is hardly surprising to anyone who is familiar with the concepts of food forests or permaculture.

Department of Crop Sciences Agroecologist Sarah Taylor Lovell, who is behind the project, said that it is important to figure out better approaches to agriculture before we reach the tipping point on food security and climate change. She pointed out that people could earn money for carbon credits or ecosystem services in the future, so savvy landowners might want to get on board now.

Lovell is one of several authors of the study, which was published in the Agroforestry Systems journal and presents a concept known as “multifunctional woody polyculture.” Under the system, shrubs and trees bearing nuts and berries are incorporated into an alley cropping system that has row crops such as hay. This imitates many of the features of a natural system, including its habitat features and capacities to hold nutrients and store carbon, while still having commercial viability. For example, there are practical agronomic considerations like placing the shrubs and trees 30 feet apart in linear rows to accommodate equipment.

The researchers are conducting a long-term experiment with seven different combinations of species and commercial-scale plots. Some entail simple combinations with two species of trees and others are far more diverse, with several species of shrubs, trees and forage crops. They are also hoping to determine just how much diversity is too much when it comes to being able to reasonably manage everything.

They are already three years into their project, which will measure economic potential, management strategies and crop productivity. They are tracking how many hours of labor go into each combination to determine their economic viability.

Farmers who are used to seeing quick benefits from traditional row crops might be put off by the long wait required for nut crops to be fruitful. In fact, hazelnuts and chestnuts do not start to produce decent harvests until anywhere from seven to 12 years after they’ve been planted. However, Lovell points out that other species can be used to rake in profits in the meantime, such as vegetable and hay crops that can be harvested in the first year. Shrubs, meanwhile, can start to bear high-value fruit crops like currants in just a few years.

This type of system has already proven successful in long-term experiments in Missouri and France, but there is little formal research into the approach.

Familiar concept

All of this sounds like a smart way forward, but it’s hardly groundbreaking. In fact, it draws heavily from popular concepts like permaculture and food forests.

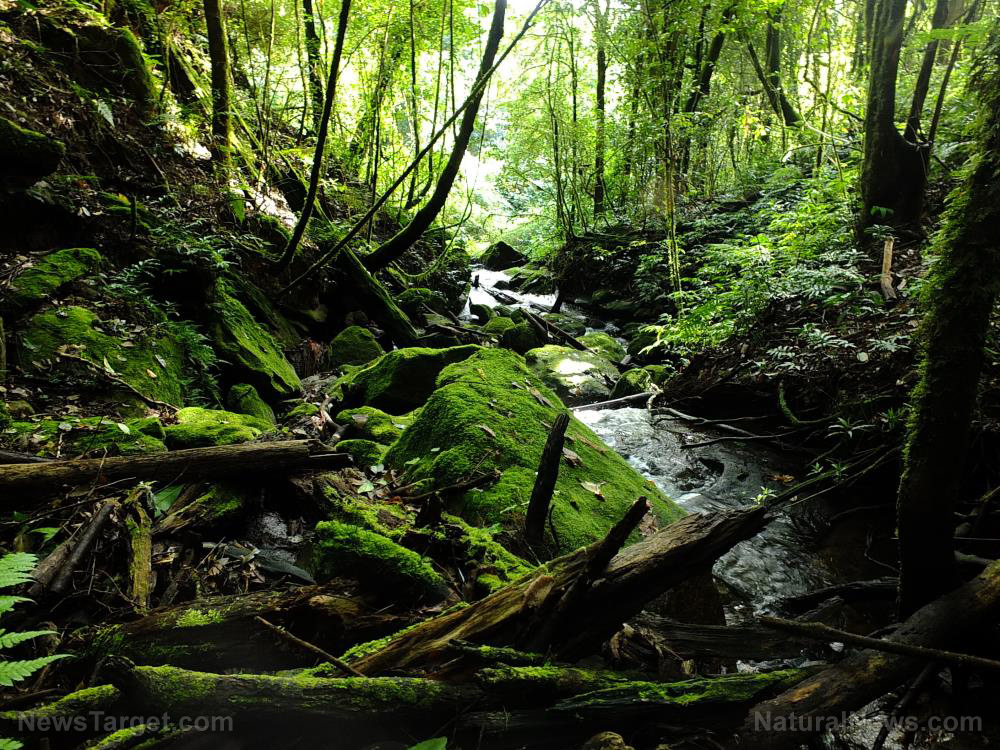

Permaculture works with nature instead of against it. It entails observing the patterns of nature and following them as closely as possibly to create agriculturally productive ecosystems that are every bit as diverse and stable as natural ones. Food forests are a key permaculture concept that is productive and diverse.

Food forests have gained popularity as a low-maintenance means of growing vegetables, fruit and other plants. While they take some time to establish, these ecosystems essentially maintain themselves once they get going and can provide a lot more food than a traditional garden.

Hardy plants like legumes are grown first to add nutrition to the soil and block hard winds, moderating the temperature so that more delicate trees can eventually be added. Fruit trees are selected based on what grows naturally in the area. Layers are often used – for example, large pecan trees might have small mulberry trees beneath them and then some herbs, mushrooms and broccoli on the ground. The plants work in harmony, with trees giving vegetables shade and vegetables giving mulch to trees. Chickens can be added to eat insects and produce eggs.

While it may not be an entirely new approach, there is no doubt that a concept like multifunctional woody polyculture is good for the planet.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: agriculture, berries, crops, ecosystems, food forests, multifunctional woody polyculture, nuts, permaculture, sustainability, University of Illinois